The significant disruption of the coin supply chain in the United States as a result of the pandemic is well- documented. What is less well- documented, or even understood, is why these shortages have persisted even as economic and consumer activity have returned.

The US Coin Task Force was convened in 2020 by the Federal Reserve and the United States Mint – along with financial institutions, armoured carriers, retailers, and consumer groups – to identify, refine and promote strategies to resolve the coin supply chain issues. Amongst other actions, it commissioned a paper – The State of Coin – earlier this year to examine the causes of the circulation challenge, following this up with a second paper – US Coin Circulation: The Path Forward – which was published last month, and offers a solutions roadmap.

Coin & Mint News™ spoke to Brian Weaver – Vice President, National and Strategic Operations, Business Resiliency, and Risk Management at the US Federal Reserve’s FedCash Services Group – at the Coin Conference in Amsterdam (where, together with Kristie McNally of the US Mint, he gave the keynote presentation) about the current state of coin in the US, key findings from the review, and the next steps.

Q: When did it become apparent that there was an issue with coin circulation?

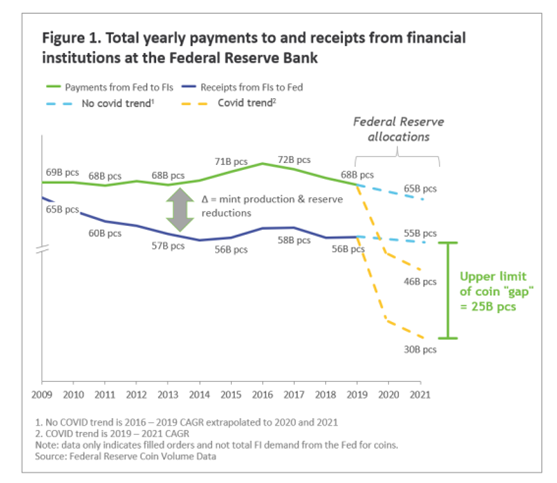

A: Early on, in Spring 2020, we saw coin deposits from our financial institution customers drop significantly, around 40- 50% of what it would be normally.

We have a business continuity group within the industry that we meet regularly with. Normally we would meet every other month or so, but we started meeting weekly, sometimes twice a week, to understand what was happening and get their feedback. All the banks were telling us that their customer coin deposits also dropped 40-50% from their sources of coin.

Around that time, Congress pushed out the first stimulus payments to taxpayers, and while many were made via electronic payment, a lot of physical checks were issued. If people receive a check, they tend to want to go and cash it. This is going to increase demand for paper currency and for coins. We saw demand for coin return somewhat to prior levels and so that gap in available coin grew significantly.

Q: Did you have a plan in place for if an event [the pandemic] like this occurred?

A: We didn’t plan for a 50% drop in deposits. We typically hold around four to six months’ worth of available inventory as reserves. That is a fairly significant amount of coin, but we went through that in about two months.

Q: If people couldn’t go out and spend money, why was the demand for coins so strong?

A: There was the initial drop in demand, largely due to the lockdowns and people weren’t going out as much and spending coin. Additionally, traditional pathways for coin circulation through commercial avenues such as tolls, mass transit, parking meters and laundromats continued their pre-pandemic transition to digital payments, and this structural change accelerated during the pandemic.

Effectively, the initial cause of the shock was the erosion of consumer pathways to return coin to circulation.

When those lockdowns began to unwind and people were able to get out and shop again, that’s when it picked back up. At the same time, retailers increased their adoption of self-checkout machines, which require three times as much coin inventory to operate – thereby sustaining a level of coin demand.

However, the drop in deposits, and incoming recirculated coin, was much more significant than the drop in demand. So, we still had a large gap in available circulating coin.

Q: Why didn’t coins return even after demand increased?

A: Pre-pandemic, for every 10 coins that we sent out, we would normally receive 7 to 8 coins back in for recirculation, and the difference there of two to three coins is what we order from the Mint – between 10-14 billion annually. In 2020, for every 10 coins that we sent out, we’d only receive 4 or 5 back in. That meant that the Mint would have to double or triple production to be able to meet the difference, and they simply can’t do that.

In June of 2020, to ensure a fair and equitable distribution of existing coin inventories to our depository institution (DI) customers, there was the need to allocate available supplies. Demand subsided a little during the holiday period at the end of the year, so it seemed as though things were improving. In the first quarter of 2021 we removed those allocation limits because that circulation gap had narrowed, and the Mint increased production.

That lasted for three or four months, but in April 2021, demand shot back up. People were going out more and shopping, and they also received their final stimulus payment. A lot of economic activity meant a lot of coin went out.

Deposits stayed fairly low, but demand returned to pre-pandemic levels and we had an enormous gap in available coin. We had to re-implement our allocations, which we’ve had in place since May 2021.

Q: Are you continuing to see that gap in available coin?

A: The challenge with our allocations now is that we have lost insight into what true demand is. DI customers may want to order a higher amount, but we only allow them to order up to a certain level, based on their historical demand and available inventories of coin.

What we’re hearing from the industry is that their demand is now somewhat similar to pre-pandemic levels. Things have improved marginally, but not to the point where circulating coin is flowing back into the Federal Reserve at normal levels, and that we can then pay out.

Q: Did you consider shifting denomination production, from the one cent to higher value coins?

A: One of the solution pillars in the ‘US Coin Circulation: The Path Forward’ paper is to rationalize the denominations and reduce production of the low denomination coins, primarily the penny, and reallocate some resources to the higher denominations.

Our understanding from Canada’s example of eliminating their penny is that they can focus production capacity more on their higher denomination coins, and be more flexible. 55% of the US Mint’s capacity is in producing the penny, and if those resources could be used to ramp up production of the higher denominations, that would help get us out of this current challenge more quickly.

We’re in an imperfect situation now with our current allocation methodology and we recognize that. We’re working, through the Task Force, to help resolve that, but it really does need to be the ecosystem as a whole working together.

The paper recommends further study on both rounding and the true cost of circulating the penny. That cost – in addition to the cost of production, which is higher than its face value – is the additional cost of ordering, transportation etc. and is in the 2-3 cent range.

The paper also asks if there are other incentives, such as price incentives, that could change behaviors in the industry. For example, charging a fee for ordering pennies to offset the cost of production. Those decisions would have to be considered or made by the US Mint.

The question of the penny in the United States has been debated for decades, and any denomination shift will be influenced by retailer demand and ultimately may involve legislation from Congress.

Q: Given the concentration now on sustainability, would that make the case for getting rid of the penny much stronger?

A: Yes, that is also in the paper. There are recommendations to further study the environmental cost of the penny, not just from the mining and raw material perspective but the minting, transportation and storage of it. If around 55% of our production is in the pennies, while not a one-for-one correlation, we can estimate that a similar large percentage of armored carriers are dedicated to moving pennies around.

There is also the vault space, and pennies don’t recirculate as much as the higher denominations. Pre-pandemic we would receive around 6.5-7 pennies for every 10 that we sent out, compared to 8 for dimes and quarters.

Q: Why engage an independent consultant to review the coin supply?

A: With the reimplementation of our allocation limits came the recognition that we didn’t have clear insight into the root cause of the issue. Depending on where you sit in that ecosystem you have your own view of what the problem is, and those views didn’t always align.

Jointly with the US Mint, the Federal Reserve’s FedCash Services business line facilitated a six-month study of the circulation challenge. In close partnership with stakeholders across the coin ecosystem, the study diagnosed the root causes of the disruption to coin circulation and developed recommended solutions to build a more resilient, transparent and efficient coin ecosystem in the US.

Through this engagement with our third-party consultants, they provided an independent and unbiased view that validated our efforts. They gathered data to really understand where the inventories were and what was happening with the flows, and were able to give us better insight into those root causes. We’d always estimated that consumers held a lot of coin at home, but now we had the data to back that up.

We were really pleased with the work of our consultants and their engagement with our stakeholders. Stakeholders were interviewed and shared their view on the nature of the problem, issues unique to their sector, and recommendations for solutions.

Data was supplied by the various groups and organizations throughout the process, so the consultants were able to put that together and we could see who is holding this coin, and how the flows of coin circulation and the source of deposits into the Fed changed as a result of the pandemic.

The qualitative assessment coupled with the quantitative analysis of data helped solidify our understanding of how changes in coin circulation were the result of an acceleration of secular shifts in consumer payment trends already underway prior to the pandemic, as well as those shifts that were more temporary in nature.

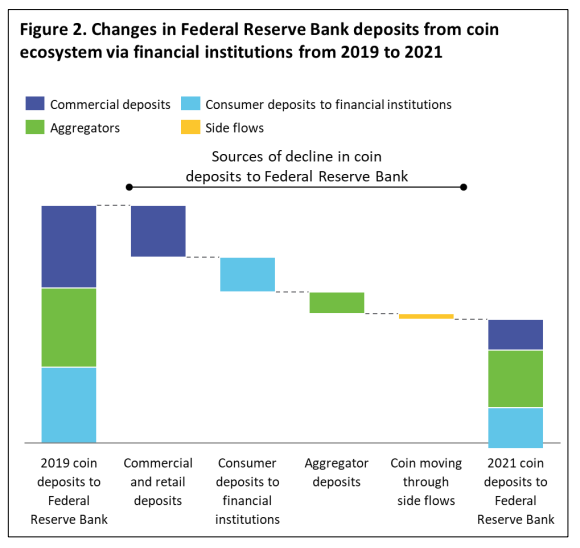

One-third of our incoming deposits were from commercial deposits through financial institutions (eg. mass transit, tolls, coin laundry, casinos, etc.). One-third came in from financial institutions through their branch network, with consumers coming into the bank and depositing their coins. The last third came in from coin redemption at aggregators, often located at grocery stores, where people empty their coins into a machine.

The largest deposit drops were in the first two, with commercial and consumer deposits into financial institutions dropping significantly. Through the pandemic, many bank branches were closed, either temporarily or permanently. DIs continued their move away from coin transactions, including accepting loose coin deposits given the cost to banks, complexity, and operational risk compared to other value- added services they provide.

Q: In terms of coin machine deposits, is there a disincentive due to the cost?

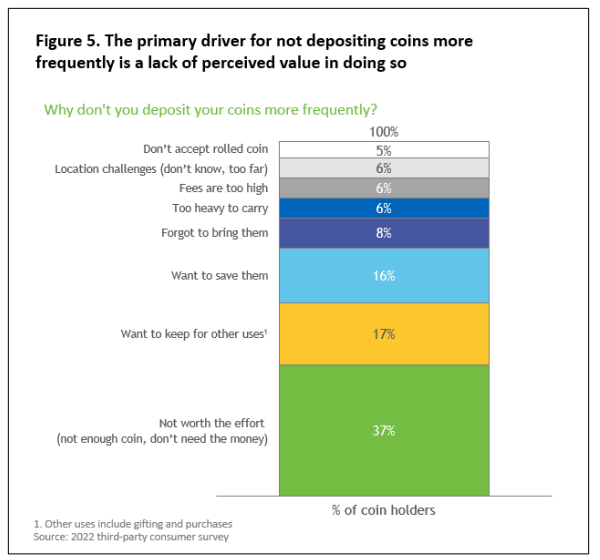

A: The third part of the analysis that our consultants carried was a 5,000 person consumer survey. It asked consumers about where they receive the coin from and what they do with it once they have it. We estimated that consumer coin jars expanded by as much as 15-20% during the pandemic. This increase is likely due to the perceived lack of utility of coins as a method of payment, especially low- denomination coins.

Only one-third of consumers responded that they plan to use their coins for payments. This reluctance is likely due to an accelerated growth of digital payment options, as well as general inflation that has decreased the buying power and utility for coins as a method of payment.

As a result, consumers are holding on to more coin at home, with an estimated value of $60-90 in coins per household. Only 6% of consumers identified fees as a barrier to redeeming their coins, while 37% indicated that depositing or redeeming their coin was not worth the effort. This group will be a key area of focus to work to unlock idle household coin holdings.

The biggest barrier to deposit appears to be apathy.

There is so much more coin out there, and we are struggling with the message that this is not a coin shortage. The billions of dollars of coin out there are just sitting in couch cushions, cars, and jars at home.

Q: Did you learn much from looking at other countries?

A: We realized the scope of the challenge but learned more in the solution sets.

One of the challenges that we continue to have is the lack of visibility across the ecosystem to better understand the root causes of the problem.

The Federal Reserve and the US Mint only have data and insight into our own holdings, as well as the orders and deposits that we receive from DIs. We don’t have data and insight into amounts and locations of DI holdings. Nor do we have visibility into what the true demand is from retailers. We did learn from other countries’ coin circulation and management examples, and also noted key differences in the coin ecosystem.

Some international models share coin data among ecosystem stakeholders and have greater transparency across inventories and demand, while others maintain a joint operating model, with a stronger role from the mint and central bank, working closely with depository institutions in managing inventories.

Another challenge and difference in our systems is that the US has over 10,000 depository institutions, which is far more than other countries. A joint operating model and data transparency across all US coin ecosystem participants would produce new complexities. However, if the US can do that with the national and some regional currency in transit (CIT) companies, the challenge becomes a more manageable opportunity. That data visibility and sharing of information is our first step.

Additionally, the US has a higher number of unbanked and underbanked individuals relative to peer countries, both in raw numbers and percentage of households that rely more heavily on cash and coins as a method of payment.

Q: Is improving data visibility and transparency one of the recommendations in the report?

A: Yes. That’s really the first of the recommendation pillars, and then the second pillar is improvements to inventory management that this data transparency enables.

Ultimately, the aim is to have true visibility across the ecosystem. Stakeholders don’t have that visibility around which DI has what inventory right now, where there may be regional imbalances between supply and demand, and how and where demand may shift over time. With data visibility, the ecosystem can get to that point where they can self-manage and partner together to better meet consumer and commercial demand for coin.

Q: Has this brought the system together to try and solve the issue?

A: It is important that the US Coin Task Force and the broader coin ecosystem continues to work together in pursuit of these solutions. Organizations need to represent their respective industries in being part of the solution. Success of these solutions is dependent upon open communication across the ecosystem to ensure alignment and coordination. This includes a willingness to share data and support transparency across stakeholders, and agreeing on solutions that promote a resilient, transparent and efficient coin ecosystem.

Our coin circulation challenge is larger than any one organization, and all stakeholders will need to work together to solve the issue.

Q: What is the main takeaway from the report?

A: The main takeaway is that the coin circulation challenge in the US is a complex problem that presents an opportunity for the ecosystem stakeholders to invest in a set of solutions that can transform the future circulation of coin. Working together with the coin ecosystem, the Federal Reserve is committed to creating meaningful change to solve the coin circulation challenge.

In order to see meaningful improvements for the American public, we need to start piloting the consumer piece, and we’re going to need to rely on the industry to help with that.

Banks have better insight into their customers than the Federal Reserve does, and we need their help in getting the message out to consumers around returning their coin into circulation by depositing it, exchanging it, or donating it. Community banks and credit unions have had successes with their ‘Get Coin Moving’ campaigns, and they’ve also been helpful in getting the message out to their customers and industry associations. We are hopeful that the larger financial institutions will also prioritize future ‘Get Coin Moving’ campaigns to their customers.

Another key takeaway is that this circulation issue is not going to unwind and resolve on its own. We can’t wait it out. We have to take action right now. That is what the FedCash Services team is focused on. We are working with DIs and CITs to share data on coin flows and inventories, to create a cohesive view of coin supply. We have to partner to improve the distribution of coin, reduce imbalances of coin supply, and see if we can get more of that coin moving.

Four key recommendations:

1. Increase transparency into coin inventories and flows across the coin ecosystem.

2. Develop new coin inventory management practices.

3. Shift the mix of denominations produced by the US Mint toward higher value coins.

4. Raise consumer awareness and reinforce options for depositing loose coins conveniently.